This piece was originally published on 21 September 2018 at WorldKitLit.

……………………………………………………………………………………….

A reflection on the importance of a full range of world stories in beautiful, artistic translation:

By Michelle Anjirbag

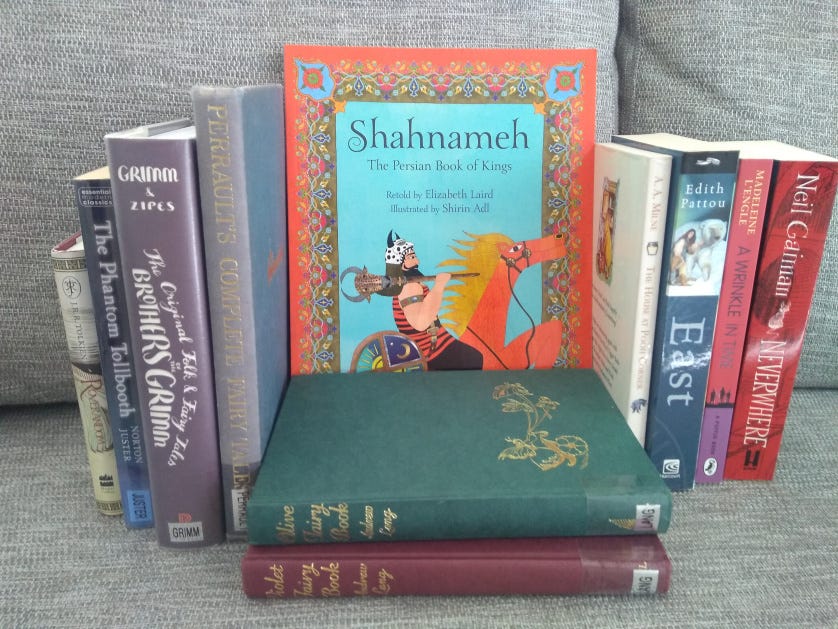

I wasn’t supposed to be buying books, but somehow, I can’t resist at conferences — even those I’m not actually attending. I’d scooped up a highly recommended graphic novel depicting refugee journeys, and an illustrated book of stories tied to constellations across cultures. And then the burnt orange cover, arabesque textures, and a very particular shade of blue spine caught my eye. An illustrated, comprehensive retelling of Shahnameh, brought by a vendor to a Picturebooks Conference at the University of Cambridge, sat on the table. And somehow, both a little more lost and a little more found, I could breathe easier.

My last name, loosely, means “fig garden”. This was not something that I knew as a child growing up on the Connecticut shoreline with very loose connections to a larger sense of my culture. I was a child taught to describe myself as Parsi and let people know they could think of me of Persian if that made it easier to place me, a child who knew the fairy tales of Perrault and the Brothers Grimm, and Greek and Roman myths but didn’t know that her people, too, might have stories equally filled with wonder and power and daring deeds. It wasn’t that I knew nothing of my heritage and culture; there were some books brought by relatives, mainly the creation stories and ones about Zarathustra’s life, but truthfully, they were in limited supply. They were written in or translated into English, but it wasn’t the same language and syntax as what I had grown up reading as a voracious consumer of texts. It wasn’t what I had been conditioned to see as beautiful language and it didn’t follow the mode of storytelling I had been acculturated to. The translations and transliterations were clunky and the art was different. So, while they communicated their points and I had a sentimental attachment to them, I didn’t have the same sense of ownership over them as felt regarding other texts, such as stories about Robin Hood and Merlin, fairies under hills or fleet racing women who could outrun the wind and had to be tricked to be beaten.

It was a love of fantasy and fairy tale adaptations that led me to be able to learn about the textures and flavors I didn’t know I was missing, the things that could help me to bridge the gap between the things I was told were part of me and mine to remember and preserve, and the things that actually felt like a part of me as a typical New Englander. I was a hybrid child, to be sure — but that didn’t mean that a part of myself didn’t feel foreign when I had to explain it, even though I could do it by rote from a young age. Identity is hard to describe; it’s harder still when we ourselves have to embody the bridge between conceptualizations of languages and culture without knowing fully to what we are affixed. I’m still learning how to build that bridge for myself, which means, in many ways, I am still learning to see that all parts of myself, all the identities that I embody simultaneously, are normal. I never questioned my identity, or that I found myself in books as a child. But as the publishing landscape has changed, I’m finding more opportunities to see myself, my people, my family, in the stories I find. And that experience has been heartbreakingly profound, across three books in particular: Susan Fletcher’s Alphabet of Dreams (2006), Tanaz Bhathena’s A Girl Like That (2018), and a translation of Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings retold by Elizabeth Laird and illustrated by Shirin Adl (2012). One made me hate looking for myself in books, one made me see myself in a book for the first time in my life, and one gave me back a glimpse of a sense of wonder when I was least expecting it.

Prior to coming across Fletcher’s book, I was really, really used to dealing with questions like, ‘no, what are you, really?’ and some far more insulting things about vultures and fire worship and demon worship, which, to this day, I don’t have a good (read: polite) response to. And when I found Fletcher’s book, I wasn’t looking for something that would connect to my culture. I was more intrigued by the thought of the girl and her brother disguising themselves, and of a child that could dream what would come. Reading it, however, left a bittersweet taste in my mouth; even as a young adult, I recognized bits and pieces of the culture I grew up with twisted to fit someone else’s narrative. Something was taken, twisted, mutated, and written into a narrative that supported some other culture’s dominance. I think this was the point where I actively stopped exploring Middle Eastern or Persian folk lore and legend. I didn’t want that experience again. I embraced Norse mythology and the tapestry underpinning the British Isles and I really didn’t look back. Not seeing myself at all was better than seeing a misleading distortion, being mythologized to fit someone else’s story.

I forgot about that for a while, until asked to review a #ownvoices YA book about a half-Zoroastrian/Parsi girl living in Jeddah and having to navigate all of her multiplicities, all the things that come of being labeled “a girl like that.” What was meant to be a quick job turned into me sobbing on a train between Cambridge and London without being able to understand why, necessarily, it felt like a new door had been opened onto my life and all the inner conflicts I’ve had throughout when it came to naming myself. Because reading the names of your extended family, seeing their exclamations and phrasings on a page, having a book affirm that your life, your experience, is valid and real, well, it hurts. I don’t know if there is a better way to describe it. And perhaps, if I had lived elsewhere, perhaps, if I could take the time to learn other languages and open the doors to other literatures, these experiences wouldn’t be quite so jarring. But I was taught to assimilate to the local; it was supposed to be enough. And I am hardly the only person who receives that messaging. If we stop to think about all the different nuances of identity and experience confined by the language we think of them in, we see quickly how categorizing people, categorizing otherness, can become an erasure. If we can’t remember what we’re forgetting, if we’re not given the tools with which to educate a society to all the things they are yet to discover, how do we ever create new spaces? What does own voices, mean, in such a context, or even, translation? We need a broader language to talk about ourselves, and to build these bridges, so that we can build our local selves while not losing the ability to talk about who, else, we are — and so that it can be understood better by others. Otherwise we miss our pasts, we miss our parallel selves – the people we could have become — and when we do connect with that part of ourselves, we risk becoming too overwhelmed with dysphoria to truly understand where we might have fit in, where we too, were once normal.

Which brings me back to buying a book I wasn’t supposed to buy at a Picturebooks Conference. Somewhere in the great vast multiverse, there is a version of me that grew up being told different stories, that grew up speaking different words, that internalized the knowledge that at one point, the things which I was consistently confronted about being “not real,” were once widespread, and known. She would have grown up not just knowing vaguely that her family bears the names of kings and queens and heroes, but understanding how that heritage can build a stronger sense of herself. She would have dreamed about a horse named Rakhsh, as well as Bucephalus or Black Beauty or Misty of Chincoteague. She would have been inspired by Simurghs, as well as Phoenixes. She would have imagined in not different but more patterns and textures and flavors, considered more possibilities, had perspective to ask more questions and wonder from different angles. And don’t get me wrong, I like who I am, I like what I’ve achieved and I’m happy with the road I’m walking now. But still, tracing fingertips over Shirin Adl’s illustrations, I can’t help wonder: with more access to more translations as a child, who, else, might I have become?

Michelle Anya Anjirbag is a PhD student at Center for Research in Children’s Literature at Cambridge in the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge, studying children’s literature. She has been an experiential educator, a ballroom dancer, an audiobook editor, a running shoe expert, a local news reporter, a book reviewer, and a writer and editor. Talents include baking cookies, reading while speed-walking through cities, and managing to still be a better journalist than Rory Gilmore. Her bylines include Roar Feminist, Fourth and Sycamore, Byrdie, and GOOD.is. One time she accidentally found herself on a radio panel. You can find her on Instagram: @michelle_anya and on Twitter: @anjirbaguette (she likes bread).