This piece was originally published on Medium on 22 March 2019.

It was the first day of spring on the Gregorian calendar, and, this year, also Parsi New Year – Navroze – though wintery winds still held the trees in their grip and the sky remained grey, threatening not just rain, but the kind of storm that hovers over the region and only dissipates slowly. But nevertheless, it was the first day of the new season, and therefore of the new year, when we are meant to turn away from what has been, and towards all the potential that might yet be. While I was growing up, my mom worked really hard to make Navroze special. We were far from relatives, far from a larger sense of our community, and she did her best to instill in us that the day was special, even if other people around us weren’t celebrating it. As we got older, and our lives changed, there wasn’t the same emphasis put on it, but the joy of celebrating the new year with the return of the promise of spring remained. It remains for me even when I am not home – messages from family all over the world have become a reminder of how much stays the same even though the years cycle on. We are a global family; it is not the location that matters, but what we can share in spite of our locations.

Perhaps that is why the idea of leaving home for a degree on the other side of the ocean with no intention of coming home in between wasn’t that difficult of an idea for me when I originally planned on moving to England for three to four years. Far better to take advantage of being on the other side, closer to adventures and opportunities that are impractical or prohibitively expensive when on the Atlantic’s west coast, than to become a transatlantic commuter. It was only a handful of years and in an intense program, they were sure to go by quickly. But one thing led to another and in the face of many things I certainly hadn’t been looking for when I left, I found myself needing to go home – not just homesick but an overwhelming urge to be where I thought I knew myself best – in the middle of my second year. Without thinking of anything other than ticket prices and term start and end dates, I found myself back in the only home I can truly remember the day before the Parsi New Year.

The new year is a time for beginnings, for good wishes, blessings, and goodwill. It is a time to reconnect with a sense of purpose, and a sense of one’s faith. It can be a time to recommit to one’s beliefs, or simply, to reconnect with family on both large and small scales. We shed the winter’s cold, though grateful for the rest it brings in its turn, and we look to the light of the sun for the promise of new life, and the promise that life will simply continue to cycle. Of course it is not simple, ever. The cycle is ever-changing. Usually the change is so gradual that we cannot really mark it happening; suddenly what was new is instead normal. But normal changes too; this new year I find myself utterly confused by the idea of how we think of home, because somewhere in the months of craving to go back home, I made a home elsewhere, too.

While my sense of family and where I might have belonged in it was global, my own sense of myself has always been very localized. I know the trees and wood of Connecticut, the smell of the loam on a cold day. I know the sound of the wind, and how one day, suddenly, it will become just warm enough that what seems like firm ground will transmute itself into marsh, and the wind will be overrun with the chatter of birds, the swoop of red-tail hawks’ wings. I know the sounds of deer snacking on mom’s roses in the early morning, and where to look for foxes’ tail at the edge of the woods at dusk. I know sunrise over the lake during a summer swim with friends, and how storms crash upon the beach. I was formed by these things as much as the libraries and schools and other buildings my life was formed within. I know the height of the stairs and all the creaky floorboards, which light switches are where even in a pitch dark room, and how to navigate without ever using them. I know how rarely strangers will try the creepy gravel driveway into the woods, where we perch, almost secretly, at the top of the hill. I know where all the books are, and the best places to hide multiple flashlights as to not be thwarted the first, or fourth, time one is discovered reading under the covers after having been sent to bed. This is my home; this is where I became myself. But even as the wind circles the house and the tap of the keyboard echoes in the same room I worked on homework and undergraduate capstone projects, papers and graduate school applications, I know that this is not all that I know, all that I am, anymore.

I wanted to come home because I thought I was losing myself in a new place, a new environment, in a way I had never wanted to. Years ago when I was considering different choices, someone I trusted looked at a list of programs and told me to look overseas – that the programs I wanted at first were brutally difficult not because of the work but because of the communities, that I would do well in them but I might not like who I was anymore at the end of them. And yet, despite thinking that I had managed to not put myself in the position of losing myself, I felt chipped away at, redefined by labels and contexts that were alien to my understanding of myself, but also alien to my understandings of how communities should work. I built a space for myself that could become a fortress of sorts, a center core where I could protect my sense of self, and let down the guarded position that was becoming permanent – only possibly because it was, is, a fortress, and I can treat the front door like a drawbridge, and only let in those who wouldn’t chip away at the cracks any further. I know the sound of the songbirds all through the year, and the smell of the fens after rain. I know the river, and that the best flowers appear before spring arrives. I know the damp air that almost freezes in the wind as it races across the flat expanse, and how it never quite gets cold in the right way. I know my space, inside and out, and the rhythms of life I share with those I care about within it. What I didn’t expect, though, was that in so short a time I could learn those things like second nature – second only to the nature of the first place I ever called home.

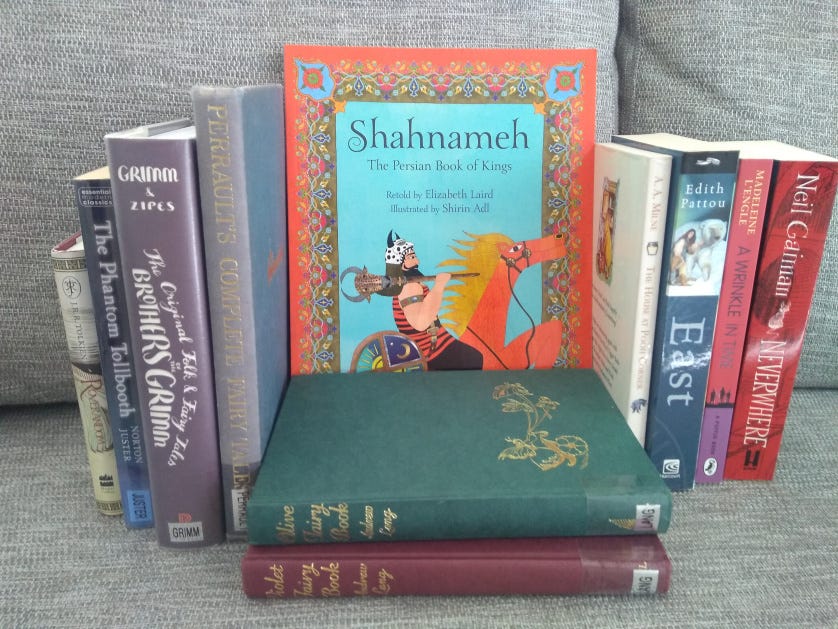

We cannot move backwards; the sun only moves in one direction through the years. This is not to say though, that we cannot go home; however, there is a day we all leave home and cannot quite return in the same way, though we may not realize it until long after it happens. I have somehow planted myself on both sides of the Atlantic; unbalanced by time zones and climate and sifting through old and new habits for different spaces that are both now home, I should perhaps be grateful that I am not truly a tree, no matter how deeply I think I’ve sent my roots into the earth. Even as I was packing I was using both the phrases “going home” and “coming home” while making plans. Both were true, both are true – old self and new self both looking to go home to roost, without realizing they were about to collide. I am home, and yet I am homesick. Perhaps this is the truth of life, that in some way we are always looking to return to some sense of comfort when face with our own growth. Like bulbs pushing through the earth, it is unsettling, uncomfortable, sometimes violent, to stretch past one’s current form and reach for the potential of what might yet be. But we can still walk through our pasts to find bits of ourselves that were lost, and make them again a part of our presents, our futures. Somewhere in the past few years, I forgot so many things about myself: that I’m a writer and essayist, that I have been competent at many things, that I am strong enough, or perhaps, just enough of a person to walk the paths I choose for myself, every day. Two days in my home, surrounded by memories and different kinds of roots – favorite books, favorite blankets, written evidence of what I’ve already managed to do – I found a small part of what had been chipped away. And I can put the pieces back together; I can gild the breaks and make them stronger, so I don’t forget about them the next time I might fracture. Though, as I write this, the same rain is pinging off the same gutter that lulled me to sleep for years and the end of Navroze is approaching, the truth is that in the place I am now homesick for, New Years’ Day has passed, and we are firmly on our way into a new future. Perhaps, this Navroze, the thing most changed is me – no more than previous new years – but this year I learn to sit with the discomfort of being aware of growing.